|

|||||||||||||

|

An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations By Adam Smith, 1776 Critique by Punkerslut

Introduction Wealth of Nations was an enormous book with a great impact on our understanding of society and the relationship of the individual with the collective. Unfortunately, it's length can frighten some potential readers, especially since it is a thorough economic treatise; to many, this makes it a dry text. After reading just the first of five volumes, I already felt much more fluent in economic concepts, ideas, and theory. The premise of my critique of the work, however, is not so much that Adam Smith's logic, reasoning, or ideas are wrong, so much as they are completely consistent and, actually, rather supportive of the ideas of Collectivism. The premises that Smith lays down in this work will be repeated and extended, by varying degrees, from such theorists as Jean-Baptiste Say, David Ricardo, and Thomas Malthus. Adam Smith is rather honest in displaying the ferocity and viciousness of class war; and he states it so brutally and clearly, that you'd expect him to say, "It is certain that some justice must be done to this." However, he was a sociologist -- he focused on how society was organized; if he had focused on how society should be organized, we would certainly consider him a political theorist instead. In this respect, I write this critique as a supplement to Smith's material.

Stumbling Upon the Precepts of Communism In several incidents, I found that Smith discovered the foundations of Collectivist idealism, but never further theorized upon them. In his observations of poverty, misery, and exploitation of the working class, he was stumbling upon the roots of Socialism, but he never looked up to see the entire tree. For instance, to quote Smith, "It was not by gold or by silver, but by labour, that all the wealth of the world was originally purchased." [*1] Smith even noted that the work of the laborer produces society's wealth, pays his own wages, and then goes to "his master's profit." [*2] This is, simply, a restatement of what Henry Salt once wrote, "Our capitalists persist to the bitter end in the fatuous assertion that to live idly on the labour of others is not the same thing as to steal." [*3] What is the essential difference between the words of Salt and those of Smith? Only this: Smith stated his observations, while Salt did that and applied a fair and just critique of Capitalism. The premise of Socialism is that the worker is the creator of all the world's wealth; natural justice only follows that an individual who applies their labor to something ought to be its possessor. Adam Smith defended the premise as an essential aspect of understanding the nature of wealth. It was logical, coherent, and most simply, based-on-fact and immediately demonstrable everywhere. Future economists, however, were much more weary of such statements. If the workers are taught that they genuinely are the creators of the world's wealth, then they may feel that they are more justly entitled to it than those who do not labor. The sense of natural justice in the common individual is too strong to present them with facts about where wealth comes from or how it is made; unless, of course, we sought to inspire rebellion. John Locke is a political theorist from a century earlier than Smith, but their ideas about individual rights have been compared by many authors. In his book, Locke wrote of property, "As much as any one can make use of to any advantage of life before it spoils, so much he may by his labour fix a property in... As much land as a man tills, plants, improves, cultivates, and can use the product of, so much is his property. He by his labour does, as it were, enclose it from the common." [*4] It is a natural, inherent sense of justice that those responsible for the production of value should be awarded that value; so to say that it is not kings, aristocrats, or lords that made wealth, but the common workers, was a counter-establishment idea. And Smith was wise enough to support it. Another quote by Adam Smith...

In this quote by Smith, we see the insufferable conditions of extreme poverty. We witness a person who produces the wealth of the world, only to receive just crumbs of their production. But the cruelty dealt to the workers of the world is not restricted to the time of Smith. It is something that has existed in every society with private property, for ages and ages. It has existed one thousand years before Smith, and many have concluded that it will exist for at least another thousand years. The living conditions of the Capitalist social order tend to repeat themselves everywhere private property reigns as king. To quote Tim Connor, author for the Global Exchange...

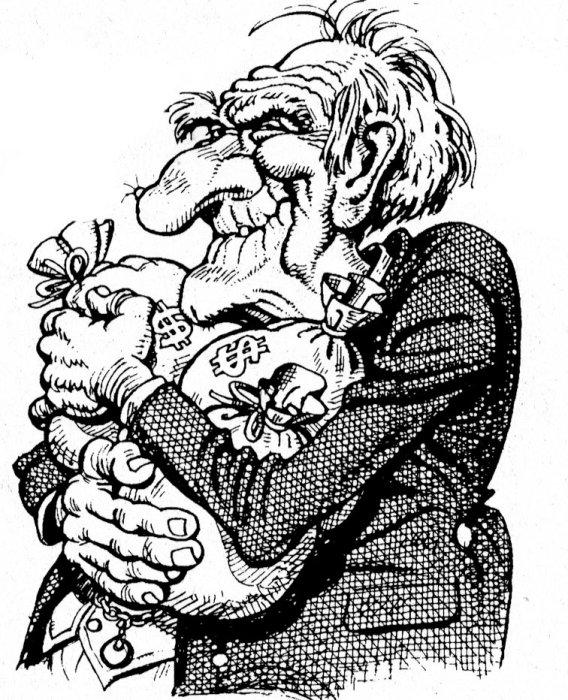

But even in developed countries, we find that there are great miseries inflicted on many innocent people; they are each the victim of an ill-organized, economic order. Elsewhere, though, I have elaborated upon such great inequalities in our society, and I will trust the reader that if they are further interested in such socio-economic observations, they can read these materials. There is the book Class Conscious, which is a probing investigation into the history of such abuses. Hopefully, though, I have impacted the reader with a sense of the horrors that can be inflicted with private ownership of the means of production; the pains inflicted by a distribution of wealth regulated, controlled, and dominated by an elite minority. From Smith's work, we find two essential facts, both of which are essential to an individual's leaning towards Socialism, Communism, and Collectivist ideology. First, we find that everything in our world is produced by one group of individuals: the working class. Second, those who produce this tremendous wealth only receive a small division of their creation. The masters of industry -- or, the capitalist class -- engage in no productive labor at all, and enjoy the most decadent luxuries. These two facts, when considered in relation to each other, are enough to arouse a thousand questions about the way that private property dominates our economy. One startling question comes to the immediate foray, "How is it that those who labor receive the least, while those who labor the least end up receiving the most?" The foundation has been set for the Socialist and Collectivist philosophies. It is curious. With a mind as observant as Smith possessed, why is it that he did not write the first chapter of an anthology vindicating and encouraging the laborers? Why is it that he did not become a master of Socialist doctrine? Instead of quietly sitting by and describing the fight between the striking workers and the hired thugs of the bosses, he could have been fighting the police, too. Or at least he could have become an organizer of the unions. Yet he remained distant from these ideas. It was still an early era. The year this book was published, 1776, was also the year that the American colonies declared independence. Thinkers were still demonstrating just how far they were allowed to test the social order. Many of the ideas that would have made Communism or Socialism feasible, such as republican government or an active citizenship, had not yet been fully developed. Even the idea of unions and organized labor was still quite illegal world-wide, as Smith noted. Sociologists and philosophers of this era were still uncertain of proceeding in any direction that was too much of a divergence of the established path. If I criticize Adam Smith for not going this extra step, then it's not a fair recognition of the brilliance he has offered to this field of learning. He played the role of an observer in Capitalism, and his thoughts and theory on the subject have greatly enlightened the world.

Smithian and Socialist Economics: Incompatible? The advocates of Capitalist theory have always heralded Adam Smith as a significant defender, master, or even inventor of their ideology. But if one were to take just a glance through some of the pages of Adam Smith, and then were to read any Socialist or Communist literature, they would find outstanding similarities. Whether we compared Adam Smith with Karl Marx, Alexander Herzen, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, or Mikhail Bakunin, it seems that too much matches up for these so-called distant thinkers. Smith and the Capitalists certainly regard private property to be an ultimate right, even divine; while the Socialists and the Collectivists instead regarded the workers' right to the fruits of their labors as a more significant and real right. Their moral systems of how the social order ought to be are clearly different, but in building up to their final conclusion, they each use the same reasoning and same evidence. They each make virtually identical observations about the social order of the Free Trade, Capitalist economy. For instance, allow me to quote Mikhail Bakunin, who is often described as the father of Anarchist-Collectivism, or Social Anarchism...

Of this book, and others like it, US President Franklin Roosevelt said, "The anarchist is the enemy of humanity, the enemy of all mankind, and his is a deeper degree of criminality than any other. No immigrant is allowed to come to our shores if he is an anarchist; and no paper published here or abroad should be permitted circulation in this country if it propagates anarchist opinions." [*9] And elsewhere, he said, "Anarchy is a crime against the whole human race; and all mankind should band against the anarchist. His crime should be made an offense against the law of nations, like piracy and that form of manstealing known as the slave trade." [*10] On March 3rd, of 1903, the 57th US Congress passed the Anarchist Exclusion Act, barring anarchists from entering the nation. In was updated in 1918 to help the United States government better control those opposed to the World War draft. The revised version states, "that aliens who are anarchists; aliens who believe in or advocate the overthrow by force or violence of the Government of the United States or of all forms of law; aliens who disbelieve in or are opposed to all organized government... shall be excluded from admission into the United States." [*11] The government has always had a strong opposition to the Anarchists and the Socialists -- to those who oppose political and economic subjugation. But how different was Bakunin's idea of the economic order of Capitalism compared to that of Adam Smith? Bakunin claimed that the worker and the lord of industry had completely opposite interests, and that the laborer was constantly the prey of the masters. This is the Socialist idea. But how far does it differ from Smith's vision? To quote Adam Smith...

When comparing these two selections, we find the same attitude: that the worker is at a loss, because they are ultimately reliant upon the capitalist for their food and sustenance. The Capitalist needs the laborer, as the laborer needs the Capitalist; but since the depth of the needs are not the same, the Capitalist has a much greater range of liberty in offering whatever wages or working conditions they desire. In effect, they create a virtual slavery. Just take and compare two of the sentences: "They [the workers] are desperate, and act with the folly and extravagance of desperate men, who must either starve, or frighten their masters into an immediate compliance with their demands." -- "The worker is in the position of a serf because this terrible threat of starvation which daily hangs over his head and over his family, will force him to accept any conditions imposed by the gainful calculations of the capitalist, the industrialist, the employer." The two statements run so gracefully side-by-side that one may even believe that they originate with the same author -- but one is the figurehead of the Capitalist movement and the other is the father of Libertarian-Socialism. More significantly, neither thinker speaks of the Capitalist system in generous, kind terms. It is a system inherently based on coercion and violence. This is far from complimenting the theory of Capitalism. The Collectivist and the Capitalist agree on the bleak outlook that life offers to those of the working class -- their untold toils, miseries, pains; they are the victims of political scapegoating, the prey of industrialist and capitalist, a second-class in the court systems. All of this can be admitted by both Adam Smith and Mikhail Bakunin. But, when we compare the Collectivist and the Capitalist understanding of what determines the workers' wages, how much variation is there? Smith wrote that the wages of the worker "must even upon most occasions be somewhat more [than necessary for sustenance]; otherwise it would be impossible for him [the worker] to bring up a family, and the race of such workmen could not last beyond the first generation." [*13] Karl Marx is arguably the father of Statist Communism. But in his economic observations concerning wages, his opinions were...

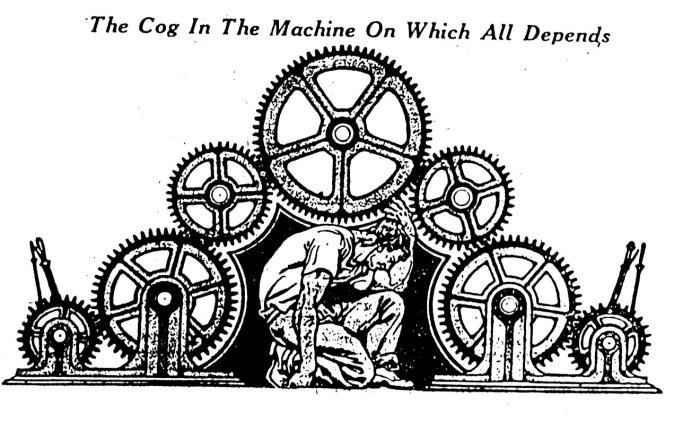

Adam Smith's arguments, compared to those of Marx and Bakunin, are fairly similar -- at least, in terms of understanding the relationship between capital and labor, between the owners and the workers; the haves and the havenots. Marx is the pariah of the school of Statist, Authoritarian Communism; Bakunin the philosopher of Libertarian, Anarchist Collectivism. The ideologies that hail from Adam Smith tend to be Right-Wing -- they are monarchical, nationalist, and occassionally liberal. The vast majority tend to be Authoritarian, though now and then Libertarian, Right-Wing movements will pop up; such as the Anarchist-Nationalists or the Anarchist-Capitalists. Despite the variety of differences between all of these thinkers, these organizations, and these cultures, the observers of the social order are in agreement in this one aspect: the slavery imposed upon the working class from the masters of society. Adam Smith wrote, "The masters upon these occasions are just as clamorous upon the other side, and never cease to call aloud for the assistance of the civil magistrate, and the rigorous execution of those laws which have been enacted with so much severity against the combinations of servants, labourers, and journeymen." Capitalism is not just an economic tyranny -- a world where those who control the wealth of society manage the land and resources so that there are numerous idle hands, plenty of beggars, and countless starving. It is an oppressive, totalitarian order -- the laws, the courts, the magistrates, the police, the politicians, the congresses, and all the kings' men are enemies of the trade union! Each one of them seeks to exploit the worker, to take and enjoy the fruits that another has labored to create; this is exploitation. But Capitalism has elevated it to the point of absolute Oppression! It is not that the worker is simply a disposable cog in a machinery that works constantly against their interests -- the entire social order, from the execution of the laws, to the development of cultural institutions, to overseers of "education," -- everything and all components are made to keep the worker subservient, subjugated, quarantined, and enslaved. Smith was convinced of these details of the social relationship between the laborer and the owner. He wrote that anyone who doubts it "is as ignorant of the world as of the subject." [*15] Smith's ideas on the subjugation of the worker almost identically match those of Mikhail Bakunin, Emma Goldman, and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. But the Anarchist-Collectivists and the Statist-Capitalists are still worlds apart in ideology. Even if we venture outside of this focus of the laborer, we find a great deal of similarity between Smith's market theory and that of the Communist economists. For instance, Adam Smith once wrote concerning the cost of production...

In the previous selection, Smith makes a simple observation of economics: when a producer has found a cheaper method of producing their commodity, they gain an advantage. That is to say, they gain an economic advantage. Not only does Marx similarly observe this, but he adds his own observations...

When an industrialist can produce their commodity more cheaply than their competitors, they only have to reduce their price to slightly below their competitors' rate. This will be enough for the one industrialist to dominate the market and reap a significant profit. Smith and the Socialists are identical in many components of their theory, especially in their observations of developing Capitalism -- the primary difference lie in the moral inference. Bakunin and Marx were bitter opponents, one seeking to become master of the state, the other seeking to abolish the state. They did hold one similarity: their opposition to Capitalism as a morally, culturally, and socially destructive system. The Capitalists accept and apologize, the Socialists oppose and agitate. It is unfortunate that much of our world's Liberal and Conservative circles fail to make such deductions, let alone even study this material. For instance, to quote Ronald Reagan, "How do you tell a Communist? Well, it's someone who reads Marx and Lenin. And how do you tell an anti-Communist? It's someone who understands Marx and Lenin." [*18] Marx and Smith, as I've demonstrated above, are very far from different in their economic dispositions -- it is their morality that differs. And with such an abstract concept as morality, a two-sentence statement is perfect to please a crowd as a politician, but its empty in value and indicates the speaker's ignorance.

The Sacred Right to Property There is no doubt that Smith's work focuses on economics as a discipline -- this book is a sociological treatise. In terms of philosophy and ethics, it falls short. It is for this reason that it is often judged solely in as an economic masterpiece. However, for the purposes of examining and observing the economic relationships of society, Smith had to make some philosophical conclusions. Since it was such a divergent topic from the thread of his study, these philosophical deductions were done quickly and seemlessly. There is one part of the material where Smith attempts to justify the system of capitalism and private enterprise. He appeals to the argument that private property has been ordained by god, and that for this reason, it is sacred. In his own words...

This is the only part of the book that seriously delves into a justification for Capitalist, social organization, and it only so lightly touches upon it. Even more interesting, this is done in chapter 10, far after Smith has already laid the elementary functions of the natural economic order. This book generally dealt with the economic behavior of the people, whether they were owners or workers, artisans or farmers. It also covered a variety of the economic regulations that were implemented and their varied degrees of success or failure. The assertion that the right to private property is a sacred, inviolable right is a drop of religion in a pool of economics. Adam Smith did defend it at this point in the text, though the way he describes it, the right to property seems to belong to those who labored to create the property -- this would necessarily mean that the workers, who create the means of production, should be its owners and managers. This is opposed to stock owners, managers, and capitalists, who contribute no productive labor but receive the majority of productive laborers' fruit. However, Smith still comes out and agrees that the Capitalist has a right to owning property which they had offered no labor to create. Of course, the statement is very diplomatically put, describing it as "encroachment upon the just liberty both of the workman and of those who might be disposed to employ him." It is the right of the worker to become employed, subjugated, and exploited. That the worker should be the possessor of all that they create -- this is inherent, logical, and just. But that the owners of the industry, the mines, the lands, and the townhalls should be the rightful posssessor of another's creation is incoherent. It is certainly illogical, especially following that just the reverse of this statement is used as a justification for the worker's right to property. How is it that both labor and idleness are equal justifiers in granting the right to property? As religious doctrines tend to go, it is inconceivable. That is the base of my counter-argument. First: Smith's idea of private property as "sacred" is a religious justification. There is little that can be gained from arguing about the clearly unknowable. Second: Smith's idea of the right to property, and its relationship to labor, is incoherent. If labor grants the worker their right to property, in what way does idleness grant the capitalist their right to property? Theoretically, the argument falls short.

On Public Management While Smith's glaring villification of the Capitalist system is often brushed aside, there is one part of him that is highly advocated. It was his devout opposition to tariffs and government regulations on the economy -- that is the only thread of Smith's economics that Capitalists will admit. The general trend throughout the work of The Wealth of Nations certainly is in opposition to the use of economic regulations. Adam Smith frequently brings up examples of kings, queens, and their advisors who fixed prices, regulated production, or controlled business. In demonstrating many of the regulations that were developed and imposed, the Smith shows how economic policies can have a negative effect, as opposed to their positive intentions. For instance, in one section of the book, Smith writes, "By the 5th of Elizabeth, commonly called the Statute of Apprenticeship, it was enacted, that no person should for the future exercise any trade, craft, or mystery at that time exercised in England, unless he had previously served to it an apprenticeship of seven years at least..." [*20] Naturally, such a restriction is quite extreme, and it produced rather poor results. Just a few sentences later, the author lamented, "It has been adjudged, for example, that a coachmaker can neither himself make nor employ journeymen to make his coach-wheels, but must buy them of a master wheel-wright..." There are other examples, as well. Smith describes a similar economic policy in monarchical France, "In 1731, they obtained an order of council prohibiting both the planting of new vineyards and the renewal of those old ones, of which the cultivation had been interrupted for two years, without a particular permission from the king... The pretence of this order was the scarcity of corn and pasture, and the superabundance of wine." [*21] His criticism? "The numerous hands employed in the one species of cultivation necessarily encourage the other, by affording a ready market for its produce. To diminish the number of those who are capable of paying for it is surely a most unpromising expedient for encouraging the cultivation of corn." Naturally, leading to his indictment, "The rent and profit of those productions, therefore, which require either a greater original expense of improvement in order to fit the land for them..." Elsewhere, through the work, we can find multiple examples of this. Smith makes one observation of another British, economic policy, "In 1554, by the 1st and 2nd of Philip and Mary; and in 1558, by the 1st of Elizabeth, the exportation of wheat was in the same manner prohibited, whenever the price of the quarter should exceed six shillings and eightpence..." [*22] What were the effects of such a restriction of economic activity? Smith comes in with the verdict: "But it had soon been found that to restrain the exportation of wheat till the price was so very low was, in reality, to prohibit it altogether." If there is one point where those of the Socialist and Communist school disagree with those of Smith's school, it is here. The state collectivists believe that a philosopher king can regulate the economy beneficially to the people. In complete opposition, Adam Smith was firm in his theory that a political or legal interference with the economy produces harmful results. The two camps cannot deny the barbarian aspect of a Capitalist, Free Trade society. But there is a hopeless division between the two schools. One insists that government interference worsens conditions for the whole of society; the other insists that government regulation is capable of producing better, social results. This is the crux of the argument between the followers of Smith and the State Socialists. Adam Smith wrote this book in 1776. What are the likely historical, social, or cultural conditions that could've effect his theory? Many others who examine Smith with a critical eye will bring up one particular, sore spot: the concentration of capital, or more specifically, the industrialization of production. Smith perhaps stood at the very moment of eclipse between the old and new worlds. The Stocking Frame, for instance, was first developed and used in 1589 by William Lee. It was the first tremendous step in the industrialization of the clothing-production industries -- the first of industries to be dominated by machine production methods. Lee, however, was denied a patent from Queen Elizabeth I and James I, both citing concerns over unemployment caused by machinery. [*23] And it would not be until the early part of the 1800's that this use of machine-tools over hand-tools dominated the industries. The Industrial Revolution in England was a triggering event for similar revolutions throughout the world. Eric Hobsbawm asserts that the period starting in the 1780's and became fully developed in the 1840's. [*24] T.S. Ashton, however, suggests that the industrialization started in 1760 and reached its heightened level in 1830. [*25] Given the fairly liberal estimate of Ashton, that the Industrial Revolution started in England in 1760, this would give Adam Smith only sixteen years to observe it. It may have appeared to be something of a minor trend, even though it would gain momentum and persist for several centuries. What is most significant concerning the development of machinery? Is it not just an additional industry, capable of servicing other industries to improve their effectiveness? Certainly, one may initially leave their conclusions there. But the machined businesses reached the point of complete, economic domination. The significance is that production now requires tremendous amounts of wealth; hand-tools are no longer sufficient as a means of self-employment, or they hold promise for only an extreme minority of individuals. The great majority had shifted from share-croppers, artisans, and farmers into machine laborers, applied to all industries and agriculture. Whereas the laborers were once the owners of their own shops and fields, we -- the people -- are now dependent upon wage labor. The term private property has become completely redefined for us: it does not mean the commodities or goods or services, or any means of sustenance. It is, very specifically, productive machinery. It is the economic force upon which all forms of sustenance are derived. It is shallow to apply the phrase private property to my clothes, my food, and my housing. Any one of these items can be produced at tremendous rates, with extremely small amounts of labor -- and if the other industries are machined, then the resources for producing these goods becomes fairly cheap. In industrialized society, private property, then, does not mean the right to possess belongings, such as food, clothing, or housing. The right to property doesn't even mean the right to ownership in Capitalism, excepting for those who own productive wealth. Private Property means that the laborer pays $2 for a loaf of bread, but the owner of the bakery must only pay $0.02. Capitalism creates a privileged caste, in terms of economic, political, and social rights. To speak of the workers' right to Private Property is actually to speak of our persecution, exploitation, and oppression by a police state and an elite, coercive minority -- exactly as described by Adam Smith. The logic follows perfectly. When the means of production shifted from hammers and saws to power generators and turbines, only the very wealthy could afford them. And those who could produce their commodities or services more cheaply than their competitor had a significant edge. The effect on the economic landscape was tremendous. It shifted from an economy of self-governing proprietor-laborers to an economy of wage-dependent workers. No historian or sociologist is going to argue the power-concentrating effects of technology on a Capitalist system. Big Bill Haywood, a giant of the American labor movement, wrote, "A hundred years ago, when coal mining began in thiscountry, any farmer on whose land there cropped out a vein, might open a mine and sell the product. Today the coal-miners work for great trusts. They use machines and other expensive apparatus." [*26] And, elsewhere in the same text, too: "For a long time, down even till 1900, farmers who owned one hundred or two hundred acres of land could make good use of the machines which had been invented.... But the machine process has now outgrown the size of the old-fashioned farm. Plows are being drawn by traction engines. Grain is being reaped and threshed by great machines which the small farmer cannot afford to buy and could not profitably use even if he possessed them." [*27] Is there a significance in this shift? If one economy is dominated with laborers who own their tools, and another is an economy with just a handful owning the means of production -- is there a significance between these two economies? Are we going to draw different sociological conclusions from them? Or, are their theoretical foundations self-contained and consistent within each other? These serious, important questions are the burden of ideologies that build off of Adam Smith's economic theory. Smith shed some light on the beginning trends of concentration of wealth into the hands of a few. For instance, "To prevent the market from being overstocked, too, they have sometimes, in plentiful years, we are told by Dr. Douglas (I suspect he has been ill informed), burnt a certain quantity of tobacco for every negro, in the same manner as the Dutch are said to do of spices." [*28] The author had stated that it was by appealing to the self-interest of others that we form economic relationships. One of his rather popular quotes is, "It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest." [*29] But I do not see this with the act of burning fields and fields of food so as to drastically increase prices. Far from an appeal to the self-interest of others, this seems -- above all else -- an appeal to the self-interest of the farm owners. One could certainly argue that by burning their fields of food, that farmers, by making their product more dear, made themselves more desirable -- and by this, they were truly appealing to the self-interest of others. Whatever semantics may be applied, it is fairly clear that the world suffers for want of food; those who intentionally destroy their own crops for profit are contributing to the starvation crisis. Whether or not it's an appeal to the self-interest of others can largely be ignored. The simple fact that it is opposed to the self-interest of others ought to be sufficient enough. Such wasteful acts drive up the price and reduce availability of a needed commodity; this is certainly against the peoples' "regard to their own interest," as Smith would put it. Elsewhere he would describe such activity broadly, "A monopoly granted either to an individual or to a trading company has the same effect as a secret in trade or manufactures. The monopolists, by keeping the market constantly understocked, by never fully supplying the effectual demand, sell their commodities much above the natural price, and raise their emoluments, whether they consist in wages or profit, greatly above their natural rate." [*30] In a more long-winded passage, he describes how this mode of thinking dominated the guild system...

The Capitalist class behaves, acts, and creates the same effect on the economy as those of the class of statesmen. The gods of state and industry both have a self-interest in preserving their economy. Each sends down orders to the lowliest of workers. To the economic master, it's a matter of wage reductions, unemployment, or wasteful allocation of resources; to the political master, it's a matter of taxation, tariffs, and prohibitions. The criticism of Smith against both these types of masters is clear. These elite, minority classes hold a firm social, economic position. The worker cannot withdraw without starvation and the citizen cannot withdraw without imprisonment. These systems are twin evils of authoritarian, violent coercion: Capitalism and the State. The Capitalist is a new incarnation of the Statist. If Adam Smith wrote his book at least twenty or thirty years later, he would have had wider conclusions. The capitalist and the statesman are unmoved in their positions. The only exception are those with enough cunning and brutal instinct to succeed in usurping a throne. There is no use in the elite class "appealing to the self regard" of the masses. Appealing to the self regard of another is only a meaningful tactic when you seek to gain something out of them. In the Statist-Capitalist system, the workers are already exploited, the citizenry are already oppressed -- there is nothing more that the heads of authority could seek in their nation. There is no way for the common people to effectively compel statesmen and industrialists. The owners of government and business, unthreatened by popular action, are generally free to exploit, rob, pillage, and carry on wars. There are some few moments in history where popular insurrection was enough to effect the bosses of state and economy. Liberal rights of free speech, press, and association tend to accelerate such revolutionary movements; and naturally, such rights are always quashed at any moment the state or the capitalist fear their survival. The liberal program of compulsory education and parliaments, however, has rarely been enough for a revolutionary movement to succeed. When we look to those who have disempowered their oppressors, we often find the General Strike...

Anarchist-Syndicalism in the Light of Adam Smith Far from being a critique on Adam Smith's book, this is more of a perspective and an interpretation. I did not seek to discredit his ideas or theories, but to apply them rationally and logically to the modern social order. By doing such applications, perhaps we can at least find some contradictions -- in our world, in Smith's followers, or even in his argumentation. When applying the rules developed by Smith, we find that his economic understanding of Capitalism is virtually identical to that of Communist, Socialist, and Anarchist thinkers. The Collectivist asserts that they are attempting to improve the lives of every member of society, by the means of worker or public-management. The Capitalist, on the other hand, asserts that any interference from a political or legal authority tends to produce negative results on the people. Smith did not live in an era where there were organized and massive, Communist organizations -- he wrote his work a century before The Manifesto of the Communist Party was first composed. It was only little more than a quarter of a century before William Godwin would compose his An Inquiry Into Political Justice, which would become the Western World's most impressive attack on private property. However, the followers of Smith do not regard these new gods of state as a different form of the kings, queens, and political giants of humanity's history. A Communist dictator is as incapable of producing a good effect with economic policy as a Monarchical dictator -- Chairman Mao, or King Henry, it makes no difference. This is likely to have been Smith's opinion of political parties of the Socialist and Communist ideology. Where does the Anarchist tendency fit in the scheme of Adam Smith's ideology? Certainly, it is far more favorable than the Socialism and Communism based on political parties and state domination. As a rule, the Anarchist is not a creature of law and coercion, but an individual in voluntary, cooperative, and mutual associations. The majority of society is this low class of workers, and the most mutual and cooperative act that such a class could collectively undertake is their own liberation. To quote Rudolph Rocker in his 1938 work, AnarchoSyndicalism...

Both the Statist-Communist and the Anarchist-Communist are highly critical of the Capitalist system; both seek to overthrow, dismantle, and destroy it, replacing it with workers' control. Against the Statist-Communist, the advocate of Smith will bring up the countless moments in history where a legal authority has imposed an economic order, and it created disaster for the common people. This is the brunt of the assault of the classical, Smithian economists against Marxian revolutionaries -- at least, in terms of an economic criticism. There may also be cultural, social, and political criticisms of Marxist or state-Socialist systems. Since this is a critique of Smith, though, I'll keep it strictly to economic criticisms. This argument does not apply to the Anarchist-Communist, though. As Rocker described, the Anarchist does not seek to criminalize, outlaw, or regulate the economic order. The philosophy of the Anarchist-Collectivist is the General Strike and using it as a means to create a worker-managed, economic order, without any laws or government. The State-Socialist, for instance, will gather signatures, collect donations, and run an election campaign. They're aiming to become one more government member casting a vote for the Eight-Hour Day. The Anarchist, in contrast to this, will organize the workers, advocate boycotts, raise class consciousness, and finally declare a General Strike. The aim here was essential the same: to compel the industrialist, Capitalist class to submit to the Eight Hour Day. The means, though, differed. The first nationally-imposed, all-industry, Eight-Hour workday came from a General Strike by an Anarchist federation of labor unions; the CNT-FAI in Barcelona, Spain, 1919. While Spain may have had nearly seventy years of intensive, Anarchist activity, from protests to striking to boycotts, the CNT-FAI was less than thirty years old. Yet it was this organization that created the first Eight-Hour Day. Marx had command of an international association of Socialist groups, far outweighing the Anarchists in support, wealth, and power. The Nationalist despot of Germany, Bismarck, often flirted with the Socialist groups, giving them pathetic and weak legislation to satisfy their rumblings. [*33] Likewise, we see the same activity in the Duma of the first Constitutional Monarchy in Russia, 1907. The majority was almost held by the socialist, labor, and progressive parties, 216 seats against 237 seats held by moderate and right-wing parties. But even in such favorable conditions, the best the leftist parties could achieve was a national insurance scheme for the workers. [*34] Mikhail Bakunin spread the seeds of Anarchy in France, Spain, Czechoslavakia, and Poland, personally escaped from the Tsar's brutal prison, and remained a fugitive throughout his entire life. For a moment, Bakunin and Marx sat at the same table in the First International Workingmen's Association; but philosophically, they were too opposed, and the entire organization was dissolved. Bakunin significantly contributed to several national insurrectionary movements; he died at age sixty-two, in a hospital in Switzerland, after organizing a revolt in Bologna, Italy. When he brought the ideas of Anarchist-Collectivism to the workers of Spain, it would be only several decades later that their General Strike achieved the first Eight-Hour Workday. In contrast, we see that Marx lived lavishly his entire life, tended by servants and cooks, [*35] supported by his friends businesses, [*36] living as a bourgeoise. Those who worked sixteen hours a day for their wages just so they could give it to the party did not see any hypocrisy in this. Bakunin lamented, "Mr. Marx does not believe in God, but he believes deeply in himself." [*37] The Statist-Socialists seek to abolish Capitalism by granting themselves enough power and privilege to reorganize the social order; the primary organization adopted is the political party. The Anarchist-Collectivists seek to abolish Capitalism by a General Strike, organized through voluntary, cooperative, and mutual associations; in particular, the labor union. The power, wealth, and support of the Statist Communists far outweighed that of the Anarchists by a thousand to one, and in spite of such shortcomings -- it was the advocates of the General Strike who first achieved the greatest accomplishment of the workers: the Eight Hour Day. Mao Tsetung was an ardent, self-described Marxist. Even with a billion people under his complete, direct, military rule, he was ineffectual in making the eight-hour day... forty years after the Anarchists made it a reality in Spain. To quote Mao, "Our policy, including... the enforcement of the eight-hour working day..." [*38] This was in 1937. But even earlier, in 1928, the Sixth National Congress of Mao's Communist Party of China adopted this point to its program: "institute the eight-hour day." [*39] And later on, in 1940, Mao also included in the Communist Party's propaganda programme: "enforcing the eight-hour working day." [*40] In defense of his military dictatorship, Mao said in 1949, "Our present task is to strengthen the people's state apparatus -- mainly the people's army, the people's police and the people's courts -- in order to consolidate national defence and protect the people's interests." [*41] Mao's argument, in short, was that it was political authority that would achieve the peoples' liberation. Such a philosophy is perfectly Marxist. Despite achieving such power, it took eleven years of backalley killings, executions without trials, deportations, torture, and widespread imprisonment, before Mao's absolutist regime declared the Eight Hour Day in 1960. [*42] After such a history, one genuinely questions whether absolutism is capable of achieving anything on behalf of the working class. Naturally, Mao heavily opposed Anarchism or any Libertarian form of Socialism. Writing in 1920, "...my present viewpoint on absolute liberalism, anarchism, and even democracy is that these things are fine in theory, but not feasible in practice...." [*43] Judged simply on standards of efficiency, Anarchism has thusfar demonstrated itself throughout history as a superior force to any form of state-empowered Socialism. It is more capable, enabled, and active in abolishing Capitalism and giving autonomy to the laborers and the common people. For those of us who are self-defined as anti-capitalist and pro-laborer, there can be little more appealing than Anarchism. To quote the Anarchist philosopher, Peter Kropoktin...

The misguided economic regulations of kings and queens have ravaged farming fields, destroyed industries, and starved millions. If there is any certainty through human history, it is the duality of treachery and absent-mindedness of humanity's political masters. Their edicts on the economy were as faulty as their laws on the judicial system, civil liberties, and the constitution. But, what if there was an economic regulation that wasn't coerced from above -- what if there was an economic policy that was compelled from below? For instance, the General Strike of Barcelona in 1919 that accomplished the Eight Hour Work day. Or, the General Strike of Winnipeg in the same year, which led to securing union rights for workers in the coming years. Does the nature of such a socially-imposed regulation fit immediately into Smith's condemnation of legal prohibitions or controls of the economy? It certainly could not, as these are voluntary, socio-economic movements -- the absence of their political aspirations, to gain seats of government or support a dictator, is quite clear. They are not the servants of a master who can impose orders upon them. These movements are the masses of people, directed not by a single head, but by each individual. They are a social and an economic force, not a political one. It is certain that Adam Smith's opposition was to political authority, and not to other manifestations of power. It was the lawmakers, the gods of state and military, who are to hold the blame in wreaking so much misery on so many people. When a social power sought to express itself on the public order, however, Smith was careless, thoughtless, and unmoved -- it didn't enter his line of sight. For instance, he wrote, "The masters, being fewer in number, can combine much more easily; and the law, besides, authorizes, or at least does not prohibit their combinations, while it prohibits those of the workmen. We have no acts of parliament against combining to lower the price of work; but many against combining to raise it. " And elsewhere, too: "Masters are always and everywhere in a sort of tacit, but constant and uniform combination, not to raise the wages of labour above their actual rate.... Masters, too, sometimes enter into particular combinations to sink the wages of labour even below this rate." [*45] And, in purely economic terms, he still observed their behavior, "Monopoly, besides, is a great enemy to good management." [*46] In another section of the book, Smith continues...

At these points of the work, Smith does not speak of The Wage-Reduction Act, though it was unanimously passed by the Capitalist class and enforced by the state -- it was a mutual, cooperative, and social act of the Capitalist class, and at least Smith pointed out how the magistrates, courts, and police are in their pockets; doubting this social order is reserved for those who are, as Smith eloquently put it, "as ignorant of the subject as they are of the world." It must be granted that in terms of setting policy over the economic order, it is the capitalist and the property-owner, necessarily, who impose the greatest regulation and control over the means of production. Such a monopoly or trust of capitalists is a social force. And beyond this employment of social force, Capitalists constantly use political force and violence to obtain their ends: the Seattle General Strike of 1919, the UK General Strike of 1926, the West Coast Longshoremen's Strike of 1934, the Minneapolis Teamsters Strike of 1934, the Indian General Strike of 1946, etc., etc.. The list goes on and on. In each situation, the workers had voluntarily pulled their labor from the economic order, out of their own free choice; their will was peaceful, their intentions were social justice. But in each case, the absence of laborers was too demanding on the Capitalist system, and troops and police were called in -- imprisonment, tortures, and massacres. The officers who fired upon peaceful, protesting Indians were unaware that they were completely powerless to effect the storm coming their way. It didn't matter that the first, billion-citizen Democracy was about to be born; it only mattered that they had orders to shoot down striking workers. To describe Capitalism, Free Trade, and Free Enterprise as an economic system, without political implications, is unjust. We may as well call Soviet-Stalinism a moderate, economic program of centralization. Capitalism is a socio-political order, drawing influence from the most powerful social caste and turning it into an unequal political order. To separate Capitalism from its degenerative effects on Democracy is as illogical as treating Stalinism as a theory of economic organization. In contrast to both the systems of Statist-Capitalism and Statist-Socialism, Anarchist-Syndicalism admits the existence of no state. Smith did not postulate on the political order of the Capitalists, and only briefly covered its existence -- still admitting that it was brutal and universally-enforced. He admitted to their socio-economic domination, and their casual use of political violence to guarantee it. The combination of the workers are also mentioned, and little is said on their behalf, except to note their illegality. In both cases, Smith offers neither promotion nor a condemnation of the actions of one group against the other; there is no conclusion in terms of economics that the association of one or the other leads to prosperity or poverty. It would be a bit precarious to believe that the fallibility of kings and queens applies identically to social movements. It certainly befalls the Capitalist and the Statist-Communist, as they are political; but unlike those ideologies, Anarchist-Communism is completely social. An Anarchist social movement, if it could achieve a demand from the Capitalists or the state through a General Strike or public unrest, would not be imposing a political order; it would be a completely social force. This is, of course, unlike the strikebreakers and the police of the United States, or the Cheka and intelligence agencies of the Soviet Union. Anarchism does not seek the liberation of the people through a state, but through voluntary, cooperative, mutual action. There are two, popular schools of revolution. They both seek to abolish capitalism and create autonomous, workers' control over the industries. Anarcho-Syndicalism advocates unions, strikes, and ultimately, the General Strike, as a means of abolishing the state. This has been the most popular ideology of Libertarian Collectivism, but there is also the school of Insurrectionary Anarchism; this theory advocates a violent revolt as a means of encouraging widespread revolution. These are simply different methods of creating the same world. Their ideal world means the abolishment of the state, Capitalism, and all authoritarian, social structures. There is a complete absence in the role of the state, the law, and the government in achieving this Revolution -- Libertarian Communism ultimately means the Social Revolution! Active as a social and an economic force, but inactive as a political force. We are protestors, demonstrators, boycotters, picketers, unionists, and strikers -- we are the exact opposite of voters, petitioners, lobbyists, and political candidates. In a social order where the workers are the masters of their industries, it could be described as Anarchist-Syndicalist. It is likely, though, that much of Smith's economics would be far more compatible with a society run by cooperatives rather than by Capitalists. As noted above, capitalists of tremendous power form monopolies, which are counterproductive to society. With the mines owned by the miners, the farms by the farmers, and the factories by the assembly workers -- with worker-management, economic interests would be too small and divisive to create a monopoly. Smith also defended the value of workers in the social order, stating, "It was not by gold or by silver, but by labour, that all the wealth of the world was originally purchased." [*48] Smith argued for the self-interest of individuals in society as a guiding force of economic prosperity. If it is the laborers who produce the world's wealth, can there be anything of greater self-interest than to cast off the yoke of Capitalism? There was also a defense of the work ethic for laborers who managed their own businesses, versus the wage-slaves of capitalism. Quoting Smith again, "Nothing can be more absurd, however, than to imagine that men in general should work less when they work for themselves, than when they work for other people." [*49] The workers deserve the right to manage and control their own industry; there is no feeling so cheap as to be exploited, no sentiment so baffling as to be laid off and discarded as useless. Propertied society has always been wracked by poverty and ignorance, the toiling millions suffering starvation. I certainly appreciate Adam Smith's criticism of politicians and the gods of state. His arguments certainly widened the understanding of economics. They dispelled the myths of failing economic policy; but he was not bold enough to offer a suggestion on absolving the miseries of Capitalism. Perhaps Adam Smith preferred to have a completely developed thesis than one that was imperfect. I can only hope I've done well in bridging the gap between Enlightenment-era economic theory and socially-conscious theories of Libertarian Collectivism. Punkerslut, Resources 1. The Wealth of Nations, by Adam Smith, Book 1, chapter 5.

|