|

|||||||||||||

|

By Punkerslut

"Labor was the first price, the original purchase-money that was paid for all things. It was not by gold or by silver, but by labor, that all the wealth of the world was originally purchased; and its value, to those who possess it, and who want to exchange it for some new productions, is precisely equal to the quantity of labor which it can enable them to purchase or command."What is Labor? What is Wealth? All wealth is created by labor. All of our necessities and wants are produced by labor, and that is true whether we are speaking of material needs, like bread and housing and medicine, or whether we are speaking of cultural needs, like education and books and art, or whether we are speaking of purely recreational needs, like human interaction and public performances and traveling. There is not one thing of value that came about without the expense of labor -- there is not one object we endear which came about without the purchase of the body's blood and the mind's devotion. Everything of value only has that value because of the labor that went into it. This is what I intend to prove beyond any doubt. This is not to say that we value things because they were created by labor. Why we enjoy what we enjoy or why we like what we like is a much fuller, more intense, and more complicated question to unravel, which must take into consideration popular social trends, what is economically available and affordable, and our infinitely-varied individual aspirations. The latter of these might only be fully understood under the microscope of the psychologist and the psychiatrist. It is a question that could be studied and examined under every shade of light and every degree of personality without actually yielding any definitive results. I am not here to say why people value the objects that they value -- why the young child holds a sentimental attitude about a gift given by a grandparent, or why the teenager has given into one idea of fashion instead of another, or why the full-grown adult has chosen to live in this neighborhood instead of that one. There are innumerable reasons why someone values something. I am only here to prove that whatever that something is, and however they value it, the object of their affections was produced by the labors of humanity. Why we value certain things the way we do may very well be unanswerable, given the basis of how many forms of community we have made and how many styles of personal behavior we have practiced. What is labor? For the most part, it is something that we don't like to do. It is something that puts us under strain and exhaustion, it can result in injuries to the body and mind either from the stress or from the fatigue, and it exposes the mind and heart to uncertainty and the potential of misery. But, at the same time, it is considered necessary or customary by the laborer. It is considered an obligation and a duty, something that everyone must do to fulfill their role in their society and economy. Generally, labor is also productive, in that it contributes to the production of the material that sustains their societies, but this is what I am trying to prove. My argument is that labor is the only sustaining force of society. What is wealth? It is essentially anything that we might attach with some value. It is something physical that comforts us, eases the pains of life, gives us joy, makes us happy, or somehow serves one of our various needs, even if the use is reduced down to an exchange value that grants us access to something else we want. Money serves no needs, but it can be exchanged for something that does serve our needs. Wealth can be owned by individuals or it can be owned by communities, it can be classified as the fief of a local baron or it can be classified as the capital of a local capitalist. It might belong to aristocrats by merit of a favor by a monarch, or it might belong to stockholders by merit of government subsidy and entitlement. But no matter who may be the owner, the master and creator of wealth is always the laborer. A Simple Explanation and Proof

Writing in 470 BC, more than two thousand years ago, the Chinese philosopher Confucius gave an evaluation of hard work when evaluating a colleague: "Yu lived in a low mean house, but expended all his strength on the ditches and water-channels. I can find nothing like a flaw in Yu." [*1] Within ancient Greek philosophy, we can hear an echo of the same idea. In a fantastic play about birds coming together to form their own civilization and build their own society in the sky, Aristophanes imagined this new flight-based world to build up walls to protect itself against the wrath of the gods. Casting people as birds, they appeared to create such impressive greatness in their construction: "Tis a most beautiful, a most magnificent work of art. The wall is so broad that Proxenides, the Braggartian, and Theogenes could pass each other in their chariots, even if they were drawn by steeds as big as the Trojan horse." [*2] A discussion between a messenger of the birds and one of the gods' favorites elucidates the source of this value... PISTHETAERUS: A decent length, by Poseidon! And who built such a wall?One need not go back thousands of years to hear this idea among the Philosophers, though. Jean Jacques Rousseau represented the Enlightenment in France, that period only a few hundred years ago when intellectuals began remembering the glorious tradition of liberty and philosophy from the ancient world. In his 1762 book, "The Social Contract," Rousseau offered up this wisdom to explain how civil society can exist: "Whence then does it [society] get what it consumes? From the labor of its members. The necessities of the public are supplied out of the superfluities of individuals." [*3] David Hume represented the Enlightenment in Britain, and his attitude was very similar: "...if the former kingdom has received any increase of riches, can it reasonably be accounted for by any thing but the increase of its art and industry?" [*4] In speaking of commerce, he wrote, "Every thing in the world is purchased by labor.." [*5], because where wealth exists, it comes "from the power of the public..." Farmers are "employed in the culture of the land" so that artisans and craftworkers can "work up the materials...into all the commodities which are necessary or ornamental to human life." Unworked wealth comes to us while it is "still rude and unfinished, till industry, ever active and intelligent, refines them from their brute state, and fits them for human use and convenience." [*6] And speaking to the Stoic Philosophers, he said that "...labor and attention, [are] requisite to the attainment of thy end..." But it is not in Philosophy alone you can find this... In good company, you need not ask, Who is the master of the feast? The man, who sits in the lowest place, and who is always industrious in helping every one, is certainly the person. [*7]Cesare Beccaria represented the Enlightenment in Italy, most notably cherished for his attempts to reform the legal system of the age. When examining society, and deciding how to value the services performed by its particular members, for Beccaria, that is when "we view with satisfaction and wonder the mutual chain of reciprocal services," [*8] and we must have some standard of establishing value. For Beccaria, the answer was clear: we regard the profession of the laborer "not in proportion to the pomp with which they are clothed, but according to their real usefulness, and the difficulties necessarily surmounted in the pursuit of them." An unnamed translator of the Italian book opens the preface with this summary: "Private economy is the fruit of former prodigality." [*9] If we want to evaluate the reputation of a professional's skill, we can only be certain in our estimation when "we know by what kind of exertion that reputation is gained." [*10] This is from Adam Ferguson, the "Father of Modern Sociology." [*11] Explaining his thinking more specifically, "The value of every person, in short, should be computed from his labor; and that of labor itself, from its tendency to procure and amass the means of subsistence;" [*12] and "...the means of subsistence are the fruits only of labor and skill." [*13] Whenever a king "can support the magnificence of a royal estate," it is always because of "his people, by that very wealth which themselves have bestowed." [*14] Completing his thoughts on the matter... Men are to be estimated, not from what they know, but from what they are able to perform; from their skill in adapting materials to the several purposes of life; from their vigor and conduct in pursuing the objects of policy, and in finding the expedients of war and national defense.... The scene of mere observation was extremely limited in a Grecian republic; and the bustle of an active life appeared inconsistent with study: but there the human mind, notwithstanding, collected its greatest abilities, and received its best informations, in the midst of sweat and of dust. [*15]

Philosophy is merely the study of thinking, ideas, and the truth, something which covers many broad topics but which can almost always be identified by the spirit and idealism of the Philosopher. Many of the these thoughts became specialized into their own disciplines: sociology, politics, history, psychology, and even economics. The economist's study and observation is devoted to the creation, exchange, and use of material value within the scope of social organizations, from village markets to continental trade routes. "Labor is the Father and active principle of Wealth..." [*16] This is from William Petty, a British economist writing in 1662, regarded by some as "the man who invented economics," [*17] or given a more fuller description: "By tinkering with data and simple models, this little-known Englishman came up with many of the ideas -- how to measure GDP, why the money supply and banks matter, how lasting unemployment affects the economy -- that form the bedrock of modern economics," according to a 2013 article in the Economist. Such a capitalist-sympathetic magazine is unlikely to quote Petty in regards to labor as the source of wealth: "If a man can bring to London an ounce of Silver out of the Earth in Peru, in the same time that he can produce a bushel of Corn, then one is the natural price of the other..." [*18] Samuel von Pufendorf is another lesser known economist and proto-sociologist from the age of William Petty. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy gives him this description in 2010: "Pufendorf is known as a voluntarist in ethics, a sovereignty theorist in politics, and a realist in international relations theory." [*19] In regards to property and labor, his theory was also quite realistic, from 1673: "...property which a man had acquired with such labor..." [*20] And in criticism of those who live off of their inheritance, he put forth, "...content with the riches left by their ancestors, think they may with impunity offer sacrifice to indolence, since the industry of others has already gained for them means to live upon..." [*21] Dudley North is another economist from the 1600's who offered his own views on guaranteeing the greatest amount of riches for his home country, which was England, like William Petty. In 1691, he published a short work broadly titled "Discourses on Trade," which the 1800's economist John Ramsay McCulloch would call, "a more able and comprehensive statement of the true principles of commerce than any that had primarily appeared, either in the English or any other language," [*22] although this might be somewhat exaggerated. North's thoughts were well expressed in terms of the relationship between labor and wealth, "Commerce and Trade, as hath been said, first springs from the Labor of Man..." [*23] The key to establishing wealth is then easy to understand, "...if the People apply themselves industriously, they will not only be supplied, but advance to a great overplus of Foreign Goods..." Isaac Gervaise was another British economist, who left his mark on history in his 1720 pamphlet, "The System or Theory of the Trade of the World." J.M. Letiche, writing in 1952 under the auspices of the University of California, Berkeley, pointed to the importance of Gervaise: "The greatest contribution to the theory of the international mechanism of adjustment...was made in 1720 by Isaac Gervaise....Gervaise outlined the first theory of general equilibrium in the international field." [*24] In international trade, Gervaise declared that "...Labor is the Foundation of Trade..." [*25] What does humanity value? "...all that is necessary or useful to Men, is the Produce of their Labor.." [*26] How should humanity measure its wealth? "...the whole annual Labor of a Nation being always equal to all its annual Revenues... " [*27] His argument even had that classical religious appeal always found in sciences that haven't quite established themselves yet... God made Man for Labor, so not thing in this World is of any solid or durable Worth, but what is the Produce of Labor; and whatever else bears a Denomination of Value, is only a Shadow without Substance, which must either be wrought for, or vanish to its primitive Nothing, the greatest Power on Earth not being able to create any thing out of nothing. [*28]James Steuart was a British economist much in competition with the well-known Adam Smith, author of the famous Wealth of Nations. While Smith argued for lifting restrictions in trade, Steuart took the Mercantilist position in opposition to the new trend of Liberalism, with the result being that Smith was the more influential. Dr. Samar Ranjan Sen, writing in 1957, described his impression of James Steuart as "a thinker of considerable calibre whose subsequent generations have unjustly neglected, and whose basic ideas make more sense in the economic context of the twentieth century than in that of the eighteenth." [*29] In terms of basic necessities, Steuart put forth in 1767 that "...food cannot, in general, be found, but by labor.." [*30] and "We may live without many things, but not without the labor of our husbandmen [farmers]." [*31] But Steuart also argued the basic premise that all wealth, not just the basic necessities of food, only exist because of the labor of the working people. "Did the earth produce of itself the proper nourishment for man with unlimited abundance, we should find no occasion to labor in order to procure it." [*32] In terms of trade, "...wealth never can come in but by the produce of labor going out..." [*33] In terms of the attributes the working class must possess, "....industry which makes the fortune." [*34] And in terms of our obligations as members of society, "...man be made to labor, and make the earth produce abundantly..." [*35] Even with all of the disagreements in trade and competition, Adam Smith agreed on this point, writing in 1776, "Labor alone, therefore, never varying in its own value, is alone the ultimate and real standard by which the value of all commodities can at all times and places be estimated and compared." [*36] Thomas Malthus is another big name in economics, though arriving on the economic scene only a few decades after the times of Smith and Steuart. He was obsessed with population, having during his lifetime "accumulated figures on births, deaths, age of marriage and childbearing, and economic factors contributing to longevity," [*37] according to the Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. In regards to the needs of humanity, he wrote in 1815, "...we must consider only the real exchangeable value of labor; that is, its power of commanding the necessaries, conveniences, and luxuries of life." [*38] And if we are to look toward that which provides for the needs of humanity, his investigation concluded that it is, "...the laboring classes of society, as the foundation on which the whole fabric rests..." Jean Charles Léonard Simonde de Sismondi was a Swiss economist with less fame than Malthus although writing at the same time, much like the humble Steuart to the unchallenged Smith. And yet, according to a researcher at Boston University in 1925, "Probably no writer of Economic theory has been more unselfish in his desire to promote interest in the Social Sciences...than M. de Sismondi...." [*39] To read through the principles he puts forth in economics is to get a constant repetition that labor is the source from which all wealth springs, "His [mankind's] wealth originates in this industry... All that man values is created by his industry... labor alone has created all kinds of wealth...it may be generally affirmed, that to increase the labor is to increase the wealth... the labor of man created wealth..." [*40] These quotes are all from the beginning of his 1815 work, "Political Economy." Towards the end, he concludes, "We have recognized but a single source of wealth, which is labor.." [*41] Or, as written elsewhere.. The history of wealth is, in all cases, comprised within the limits now specified - the labor which creates, the economy which accumulates, the consumption which destroys. [*42]Thomas Hodgskin was an English labor activist in a period of time where labor unions were illegal, and he was also "one of the earliest popularizers of economics for audiences of non-economists and gave lectures on free trade..." [*43] To whom can we thank when appreciating the revenue that comes with trade? "The laborer, the real maker of any commodity..." [*44] because it is by the exertions of the laborer that "all the wealth of society is produced..." Nassau Senior was another British economist, a critic of Malthus who came some time later, honored as an Oxford professor and an advisor to the Whig party on matters of work hours and wages. [*45] Yet for all his criticism of Malthus, they did agree on one part, quoting from Senior's lectures published in 1830, "...the laborers form the strength of the country." [*46] T.E.C. Leslie, professor of jurisprudence and political economy at Queen's College in Belfast, Ireland, taught his students in 1875 that Martin Luther "anticipated Adam Smith's proposition, that labor is the measure of value." [*47] Such a proposition would be mentioned by some noted German economists, including Friedrich Engels, co-author of the Communist Manifesto with Karl Marx, who wrote in 1875 that, "Labor is the source of all wealth, the political economists assert. And it really is the source..." [*48] In criticizing theories about value within economics, Edward Carpenter, the British activist and philosopher, who was "involved in the rise of mass industrial trade unions, working-class political representation and the struggle for women's equality" [*49], wrote in 1889, "...it seemed obviously necessary to make labor the measure of value. Probably (pace Shaw and the rest) it is the most important element in value..." [*50] Thorsten Veblen, the American economist who had seventeen years studying between Stanford University and the University of Chicago, [*51] would give a brief summary of his opinion on labor in 1899: "...the goods [are] produced by labor..." [*52] These views haven't entirely died out. Ezra J. Mishan, the well-celebrated British thinker, was "one of the first economists to argue that there are significant downsides to economic growth," [*53] and from his 1967 book critical of Capitalist expansionism, he declared that the common people of society are to be "regarded as producers." [*54] Bert F. Hoselitz, "an expert on developing countries" and "an adviser to many national and international organizations on questions of trade," [*55] wrote in 1973 while at the University of Chicago... Labor is an activity of mankind which has existed since the beginning of the human race. In economic discussions the term "labor" is generally thought to designate the same kind of activity in both developed and underdeveloped countries. [*56]

Economists only interpreted vague points of data, like income divided by regions and dates or productivity divided by skill level and tool efficiency. But true thinkers are always willing to explore new territory, and when Economists began investigating the people who live in those regions indicated in their economic studies, or who exist at certain times on their charts, or who provide the skill level according to their graphs, or who use the tools as indicated in company financial records -- at this point of investigation and inquiry, the Economist becomes a Social Scientist. It is a transition of the study of material and the money that represents it to a study of people and the labor they expend in creating the society that represents them. Joseph Dietzgen, a Socialist philosopher and an "entirely self-educated worker," [*57] may have been one of the earliest strongest supporters of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in their criticism of Capitalism. Much of his work was deeply theoretical and didn't reflect completely reflect his political biases. Writing in 1873, "we define work as an industrial undertaking whose products the worker uses for his own consumption..." [*58] It would be difficult to truly make any assault against such a simple, direct fact. Like other Marxists, he was deeply infatuated with industrial society, also writing, "...it is not difficult to perceive how the development of industry must finally result in an organization of productive work." Among other names that should be mentioned in sociological analysis of work and labor, there is Robert Dubin, a professor of Sociology at the University of Chicago, University of Illinois, University of Oregon, and University of California-Irvine, as well as a visiting professor to London, Munich, and Tel Aviv. [*59] Similarly enamored by the concept of industrial society, he wrote in 1954, "the very stability of the total social structure is significantly affected by stability in the industrial segment of that social structure." [*60] More thoroughly explaining his views... We can appreciate the importance of stabilizing the basis of social change in industry when we recall that ours is an industrial society. It is industry that constitutes one of the most basic or central elements of our total social structure. What happens in the society is, to an important degree, a direct or indirect consequence of developments in the industrial sector.Charles A. Myers is a poorly-known Sociologist who worked on the question of labor between the twin prisms of Economics and Sociology, studying what he could learn from the subject even if his audience was virtually non-existent. But he has come into some modern usage, being cited in the bibliography of Explorations in Economic Sociology (1993) [*61] and The Sociology of Organizational Change (2013) [*62]. For those who disagreed with the sociological interpretation of work, he had some very harsh, condemning words -- he could not accept the strict economic interpretation. Writing in 1954... There are, to be sure, still some management officials who think of production largely in technical terms, apart from the aspirations and behavior of the employees whose cooperative efforts make it possible for an organization to achieve high productive efficiency. [*63]Adriano Tilgher, the Italian philosopher and essayist, has been regarded critically by some and has been admired by others for his suggestions that "the 'religion of work' in twentieth-century America had produced a society devoted to amusement and consumption." [*64] But he still had some things to say about labor: "Work is an obligation only insomuch as it is necessary to maintain the individual and the group of which he is a part." [*65] Ernest Greenwood, an American professor of Social Welfare at the University of California, Berkeley, taught sociology for nearly three decades. [*66] Writing in 1962, he took his own sociological view of labor: "...to focus on the element of skill per se in describing the professions is to miss the kernel of their uniqueness." [*67] Or, to quote him more fully... The performance of a professional service presumably involves a series of unusually complicated operations, mastery of which requires lengthy training. The models referred to in this connection are the performances of a surgeon, a concert pianist, or a research physicist.Howard Reiter, who taught for more than thirty years and was head of his department at University of Connecticut, "specializes in American Politics, with a focus on political parties and elections." [*68] His vision of the future of America in the 1970's was rather intriguing: "...the answers to some profound questions about the future of American politics depend to a great extent on what blue-collar workers do." [*69] Lee Rainwater, a Sociologist "best known for his investigations into the plight of the urban poor" and who retired "after 23 years in the Sociology Department" at Harvard University [*70], summarized what he believed to be the spirit of the American workers: "It is they who must shoulder the burden of fighting wars, because they are in fact the backbone of the nation at such times, as they are in the area of economic production." [*71] Or, writing out his opinion more fully in 1971... They [blue-collar workers] feel that the challenges and energy required for working and family life are more than enough to ask of any man or woman. And what more can a nation ask of its citizens that a man work and be productive and that men and women together raise a next generation that is also productive and responsible?The American Sociological Association (ASA) in 2009 gave an award to S.M. Miller, who has a "distinguished career in sociological practice has spanned six decades...", during which he was "an activist in some of the most important social movements of the past half century, and a leader in shaping policy debates in the United States and internationally..." [*72] Writing with a little-known Sociologist, Martha Bush in 1971, he stated that workers see themselves as "a part of the melting pot of America; as a cornerstone of the American labor movement; and as the builders of America -- the homes, factories, roads, and bridges; and as the last stronghold of the American dream." [*73] The most profound statement of his work might be found in this little sentence: "...it seems increasingly evident that productivity is limited by human factors..."

The bridge between interpreting the world and changing it is a short one. How could you change something if you didn't understand what made it the way it is? How could you alter the nature of society with your hands if you couldn't even grasp it with your mind? That would be like trying to divert a stream, without knowing its source or its destination; or like trying to fix a mechanical engine, without knowing which gears are supposed to interact with which gears. Absence of knowledge would lead to emptiness of action, and all the good-natured hopes and aspirations would quickly disperse into nothingness or destruction, far from the dreams of creative good. And so in Philosophizing about the mind, society, and economy, one becomes prepared to change those things. One can become a Revolutionary. But Revolutionary Communism was not the first choice and decision of those confronted with the facts about labor, wealth, and the economy. Thomas Paine, the American Revolutionary who fought the British monarchy with the cannon and gunshot of his words, was also highly critical of Capitalism and exploitation. Although he wasn't ready to abolish it, he gave a good reason for his misgivings about the rule of Capital in 1795: "...the cultivator and the manufacturer are the primary means of all the wealth that exists in the world..." [*74] The British Utopian Philosopher, Robert Owen, decried the industrialization of society, and offered visions of a new society, although his remedy was only to provide education and to limit some of the more offensive parts of the Capitalist system. Writing in 1816, he concluded that, "...know that revenue has but one legitimate source that it is derived directly or indirectly from the labor of man..." [*75] Another reformer, Robert Green Ingersoll, the Northern Colonel and devoted opponent of slavery and the Confederacy, as well as a Civil Rights activist, wrote in 1877.... All my sympathies are on the side of those who toil -- of those who produce the real wealth of the world -- of those who carry the burdens of mankind. [*76]Wage slavery is an evil that deserves abolishing just like that institution from which it gets its name. The Communists who were ready to do this had a very real understanding of economics and sociology when they began to challenge Capitalism. Anton Pannekoek, the Dutch Marxist and astronomer, was one of those who participated in that somewhat early period of Revolutionary Communism, before the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. Writing in 1908, "The power of the working class rests, in the first place, upon its members and upon the important role which it plays in the process of production." [*77] The process of social and economic unfolding is multiplicative: "It constitutes an increasingly large majority of the population. Production proceeds upon a constantly increasing scale..." Writing almost twenty years later in 1936, after experiencing the last imperial government, the first elective government, and the first Soviet government of Russia, his opinion was not much changed... Production is the basis of society, or, more rightly, it is the contents, the essence of society; hence the order of production is at the same time the order of society. Factories are the working units, the cells of which the organism of society consists. [*78]John Maclean was a popular and admirable, Scottish Socialist, whose "Marxist evening-classes produced many of the activists who became instrumental in the Clyde revolts during and after WWI," [*79] and he received even some admiration from the Communists, being "appointed both an Honorary President of the first Congress of Soviets and Soviet Consul to Scotland..." He describes the changing times in 1919... "The new view was typically expressed by that up-to-date capitalist, Lord Weir, who in an address to the businessmen of Glasgow insisted that the main factor in production is man-time." He was willing to add one correction to the terminology of " man-time," though, "Man-time is just the Marxian expression labor-time..." [*80] In more modern times, we can still hear the voice of Marxism. Michael Burawoy, the Sociology Professor from the University of California, Berkeley, has "engaged with Marxism, seeking to reconstruct it in the light of his research and more broadly in the light of historical challenges of the late 20th and early 21st. centuries." [*81] Writing in 1972, he gave his view of labor:"...the process of production appears to workers as a labor process, that is, as the production of things -- use value -- rather than the production of exchange value. " [*82] William Duiker, an American professor of Asian history, is well-regarded around the world in his expertise on Vietnam, having "spent over 20 years gleaning new information from interviews and from archives in Vietnam, China, Russia and the United States." [*83] In 1981, he describes the contradiction between traditionalist Confucianism and modernist Marxism... ...where Confucianism tends to deprecate material wealth as an obstacle to high ethical standards; Marxism glorifies the productive process and views man as a natural creator... [*84]

You can quote philosophers if you want to sound thoughtful, or you can quote economists if you want to sound calculating, or you can quote sociologists if you want to sound analytical, or you can quote Communist revolutionaries if you want to sound passionate. But if you want to sound truthful and honest, you may find your words being nourished by Anarchist thinking. Henry David Thoreau produced one stream that lead to that river of thinking. Describing the common laborer in 1843, he wrote, "...his axe and spade felling trees and raising potatoes with the vigor of a pioneer; with Promethean energy making nature yield her increase to supply the wants of so many..." [*85] When John Etzler suggested that for humanity "Paradise [was] within the Reach of all Men", without Labor," Thoreau gave an even more full appraisal of the creative productivity of labor... We believe that most things will have to be accomplished still by the application called Industry. We are rather pleased after all to consider the small private, but both constant and accumulated force, which stands behind every spade in the field. This it is that makes the valleys shine, and the deserts really bloom. Sometimes, we confess, we are so degenerate as to reflect with pleasure on the days when men were yoked like cattle, and drew a crooked stick for a plough. [*86]In a similar trend of Individualist Anarchism, we can hear much that is both the same and also decidedly different from Thoreau's essays, when we look to Max Stirner, the Anarchist and Egoist. Writing just three years before the great revolutions of 1848 that shook Europe and his own native Germany, he wrote, "What I produce, flour, linen, or iron and coal, which I toilsomely win from the earth, is my work that I want to realize value from." [*87] In regards to the market in a social economy, he wrote, "He labors for my clothing (tailor), I for his need of amusement (comedy-writer, rope-dancer), he for my food (farmer), I for his instruction (scientist). It is labor that constitutes our dignity and our - equality." [*88] Stirner might be known best as the Anarchist Philosopher or the Philosophical Anarchist, a human being who enveloped both of those qualities, Anarchism as a current against social control and Philosophy as a current against dullness of thought... Laboring does not alone make you a man, because it is something formal and its object accidental; the question is who you that labor are. As far as laboring goes, you might do it from an egoistic (material) impulse, merely to procure nourishment and the like; it must be a labor furthering humanity, calculated for the good of humanity, serving historical (human) evolution - in short, a human labor This implies two things: one, that it be useful to humanity; next, that it be the work of a "man." [*89]Mikhail Bakunin -- he is the father of Anarchist-Collectivism, the first opponent of Marxism for its Authoritarianism, and the first visionary who predicted how the Soviet Union would become a bureaucratic, top-down, brutal, and oppressive system. Writing in the late 1800's, he explained his thinking on economics: "...in modern society where wealth is produced by the intervention of capital paying wages to labor..." [*90] Writing around the same period of time, he put it more simply, "Labor being the sole source of wealth..." [*91] Voltairine de Cleyre, the first well-known Anarchist native to the United States, was named after Voltaire, and rightfully so, according to her biographer, Paul Avrich, because she was a "brief comet in the anarchist firmament, blazing out quickly and soon forgotten by all but a small circle of comrades whose love and devotion persisted long after her death." [*92] Writing in the late 1800's or early 1900's, she gave the world her understanding of labor and wealth... These are the land workers and the industrial workers... these workers, the most absolutely necessary part of the whole social structure, without whose services none can either eat, or clothe, or shelter himself... [*93]Eugene V. Debs was a devoted Marxist and the first Socialist candidate for American presidency that received a significant share of the vote, done while he was campaigning in prison. But he was one of the radicals who was at the founding of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in 1905, choosing the Anarchist movement instead of the Communist one, because he was, according to the IWW, "critical of the dictatorial policies of the Soviet Union." [*94] Speaking of the common workers in a speech in 1890 that was eventually turned into a pamphlet: "...'unskilled' laborers. Their importance in carrying forward the great industrial enterprises of the world has not been recognized in the past, and is not appreciated now." [*95] Explaining a world that was in the absence of work: "...the common laborer, that vast army of workingmen who work and whose work is necessary to enable the skilled laborer to work and without whose work every industrial enterprise in all lands would cease." Fifteen years later, after the establishment of the IWW, he wrote... Today there is nothing so easily produced as wealth. The whole earth consists of raw materials; and in every breath of nature, in sunshine, and in shower, hidden everywhere, are the subtle forces that may, by the touch of the hand of labor, be set into operation to transmute these raw materials into wealth, the finished products, in all their multiplied forms and in opulent abundance for all. [*96]He had many other thoughts to get out about economics in that pamphlet, titled "Revolutionary Unionism." To society, he declared that it is "...the worker who produces all wealth..." To the worker themselves, he declared that it is "...the commodity which is the result of your labor..." And to the world, he declared that it is "...the workingmen who do the work and produce the wealth and endure the privations and make the sacrifices of health and limb and life..." When explaining the role in another pamphlet from 1905, he simply and succinctly described the proletarian masses as "...wage-workers, producers of wealth..." [*97] While Debs provided energy to the Anarchist movement in the United States at the turn of the century, it is to Peter Kropotkin that can we look for this similar influence in Russia. Writing about the interdependence of human relations in 1892... Time was when a peasant family could consider the corn which it grew, or the woolen garments woven in the cottage, as the products of its own toil. But even then this way of looking at things was not quite correct. There were the roads and the bridges made in common, the swamps drained by common toil, and the communal pastures enclosed by hedges which were kept in repair by each and all. If the looms for weaving or the dyes for coloring fabrics were improved, all profited; so even in those days a peasant family could not live alone, but was dependent in a thousand ways on the village or the commune.It is an honorable act to labor -- it is a good deed to increase and expand the resources from which society, civilization, and culture draw their sustenance. Or, to quote Kropotkin, "...labor, having recovered its place of honor in society, produces much more than is necessary to all..." [*99] But in trying to determine ownership and fairness in economics, his eye is much more emblazoned and fiery than those of the economists, "The house was not built by its owner. It was erected, decorated, and furnished by innumerable workers--in the timber yard, the brick field, and the workshop, toiling for dear life at a minimum wage." [*100] The wealthy have what the workers do not have, and, "It was amassed, like all other riches, by paying the workers two-thirds or only a half of what was their due." But even if we ignored the workers who built the actual houses of the Capitalists, we would need to consider all that goes into the value of a home... ...the house owes its actual value to the profit which the owner can make out of it. Now, this profit results from the fact that his house is built in a town possessing bridges, quays, and fine public buildings, and affording to its inhabitants a thousand comforts and conveniences unknown in villages; a town well paved, lighted with gas, in regular communication with other towns, and itself a center of industry, commerce, science, and art; a town which the work of twenty or thirty generations has gone to render habitable, healthy, and beautiful.Lucy Parsons, the American Anarchist who was most likely born into slavery under the mixed ethnicity of European, Mexican, and African, "has earned a prominent place in the long fight for a better life for working people, for women, for people of color, for her country, and for her world," [*101] according to the Zinn Education Project. Writing about the basic principles of Anarchism in the late 1800's, "The earth is so bountiful, so generous; man's brain is so active, his hands so restless, that wealth will spring like magic, ready for the use of the world's inhabitants." [*102] Leo Tolstoy, the Russian father of Christian Anarchism, suggested that the fantastic stories from the Bible were invented "to keep 'Christians' hypnotized enough to ensure that they did not question the unjustifiable compromise that the church had reached with the state." [*103] For him, the labor question was easy to answer when he was addressing the Tsar of Russia in 1901: "... the strongest and most industrious majority, which supports the whole society." [*104] The United States is home to the unique phenomenon of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Started in the early 1900's by Anarchists and Socialists, it became an impressive power in organizing the disenfranchised and oppressed. Joseph J. Ettor, the militant IWW activist, has been described by PBS as a person who "knew how to bring people together for a cause," [*105] and he told his listeners and admirers, "...the workers who do all of the producing. One class does all the work, produces all, suffers all the hardships necessary to accomplish the task." [*106] Nils H. Hanson was another IWW organizer, although of much less fame, but in a 1913 pamphlet, he described the role of the workers: "...the ones who produce everything needed in sustaining life." [*107] Or, quoting Barbara Lily Frankenthal, another member of the IWW movement... Unskilled labor is synonymous with cheap manual labor. Why is it cheap labor? Because it is worth little? No, quite the contrary; all the brains of the world could not accomplish anything without the manual, executive labor. It is the creative part of work, while brain effort is the directive one. [*108]Perhaps the most famous single character of the Industrial Workers of the World was Eugene V. Debs, best known for his presidential campaign conducted while imprisoned. Writing in the early 1900's with Frank Bohn in a pamphlet titled "Industrial Socialism," this was his message about wealth: "The great wealth of the United States has been created by its toilers alone." [*109] And, while being critical of the historian's subject of study, "...the historians have not been much interested in what the working people have done, although they have done almost everything worth while in the world." [*110] Within the IWW, it wasn't just about what "man" was making, but it was much more egalitarian than that. Margaret Sanger, founder of Planned Parenthood, had spent much of her early activist years with the IWW, and in 1918, under that background, she described where she believed wealth came from: "...women who labor, who do useful things in the world..." [*111] At her 1914 Trial, where she was accused of breaking pornography laws for publishing a magazine that provided information on female hygiene, she said to the court... For centuries woman has gone forth with man to till the fields, to feed and clothe the nation. She has shared with him the struggles and hardships of his efforts. She has sacrificed her life to populate the Earth. She has overdone her labors. [*112]Errico Malatesta, the Italian Anarchist in the early 1900's who had maintained a daily Anarchist newspaper for years and who participated in numerous revolts leading to extradition, is famous to Anarchists because his life "epitomized the development of anarchist politics, and reflected the setbacks and advances of the movement." [*113] His opinion of labor and wealth is accessible to anyone who would want to find out: "Workers produce everything and without them life would be impossible..." [*114] Rudolph Rocker represented the Anarchists of Germany in the early 1900's, being "best remembered as perhaps one of the best educated, most erudite and articulate anarcho-syndicalist writers and union activists of the Twentieth century," [*115] according to Anarchist sources. To quote him... Only in the realm of economy are the workers able to display their full strength; for it is their activity as producers which holds together the whole social structure and guarantees the existence of society. Only as a producer and creator of social wealth does the worker become aware of his strength. [*116]Revolutionary writers and scholars represent their own distinct, intellectual trend, sometimes too logical where compassion was needed, sometimes too sensitive when analysis was needed, but almost always standing out as unique and brilliant. Fredy Perlman, the Czech Anarchist, was one such revolutionary. "...the power of Capital is created by men..." [*117] he wrote in 1969, just one year after workers all across France rose up and overthrow their government by means of a General Strike. It is not just the power of Capital, but also the supply it commands: "...surplus value is neither a product of nature nor of Capital; it is created by the daily activities of people." Wealth is one thing, and money its exchangeable form: "Digging, printing and carving are different activities, but all three are labor in capitalist society. Labor is simply 'earning money.'" And, when it comes to societies that still establish themselves through economic domination and the authority of commerce... In capitalist society, creative activity takes the form of commodity production, namely production of marketable goods, and the results of human activity take the form of commodities.

Labor is the only source of wealth. But that only leads to so many other questions. If labor is the source of wealth, then doesn't that mean that the workers should own the wealth they create? If the workers own the wealth they create, then what right does anyone else have to that wealth? If the laborers try to claim what we produce, then isn't there going to be a great struggle between those who work without owning and those who own without working? If there is a great conflict between those who believe in the workers and those who believe in the owners, doesn't that mean that the world the of the workers' vision is a utopia for the part of humanity that struggles, sweats, and suffers for all of society? More and more questions pour forth. Revolt and revolution, class war and Socialism -- it seems that a simple statement about labor, which seems so obvious, may have rather complicated results for the social system that attempts to restrain it. The question of this essay hasn't just been analyzed by philosophers, economists, sociologists, and the two strains of class struggle revolutionaries, Communists and Anarchists. It is a subject of every science, every art, every cultured pursuit, and every civilized instinct. It is even the subject of Revolution and Rebellion, for who has made the revolts and struggles from our history except the working class? Who has dreamed more of a world of freedom and equality, than those who use their hands and minds to produce wealth? Who has had a greater interest in a public and communal source of social prosperity, than those who cannot have justice and equity without it? No matter where we look, no matter what experts of whatever subject we consult, no matter whether the background to the question is one where the supremacy of Capital is assumed or the supremacy of the State is assumed, no matter what no matter where, we find the same conclusion -- labor is the source of wealth. To guarantee that those who create and produce are rewarded by the efforts of their labors, this will be its own labor, and it can only be brought about by us working for it. It will become a commonly accepted creed only when people think it is important enough to talk about and valuable enough to based our social decision-making on. It may not necessarily be Socialism or Anarchism or Communism or Labor Unionism or economic cooperatives that will be the fields where we till the seeds of our ideals. But it will ultimately have to be something that places the worker at the center of the society and the economy of which they belong. Like the struggle to create the wealth of the world, a Workers' Revolution will require sweat, and pain, and blood, and misery. But the product of such a labor will be unlike any other form of toil -- that product will be justice. Punkerslut, Resources *1. "The Analects of Confucius," by Confucius, 470 BC, Book 8, Chapter 21. *2. "The Birds," by Aristophanes, 414 BC. *3. "The Social Contract, or the Principles of Right," by Jean Jacques Rousseau, 1762, Book 3, Chapter 8. *4. "On the Balance of Trade," by David Hume. *5. "Essays Moral, Political, and Literary," by David Hume, 1777, Part II, Essay I: Of Commerce. *6. "Essays Moral, Political, and Literary," by David Hume, 1777, Part I, Essay XVI: The Stoic. *7. "Essays Moral, Political, and Literary," by David Hume, 1777, Part I, Essay XIV. Of the Rise and Progress of the Arts and Sciences. *8. "A Discourse on Public Economy," by Cesare Beccaria, Date Unknown. *9. "A Discourse on Public Economy," by Cesare Beccaria, Date Unknown, Translator's Note. *10. "An Essay on the History of Civil Society," by Adam Ferguson, 1767, Part 1, Section V. *11. "Adam Ferguson, 1723-1816," by the International Association for Scottish Philosophy (IASP), http://www.scottishphilosophy.org/adam-ferguson.html . *12. "An Essay on the History of Civil Society," by Adam Ferguson, 1767, Part 6, Section I. *13. "An Essay on the History of Civil Society," by Adam Ferguson, 1767, Part 3, Section IV. *14. "An Essay on the History of Civil Society," by Adam Ferguson, 1767, Part 3, Section II. *15. "An Essay on the History of Civil Society," by Adam Ferguson, 1767, Part 1, Section V. *16. "A Treatise of Taxes and Contributions," by William Petty, 1662, Chapter 10. *17. "Petty Impressive," Dec 21st, 2013, the Economist, http://www.economist.com/printedition/2013-12-21 . *18. "A Treatise of Taxes and Contributions," by William Petty, 1662, Chapter 5. *19. "Pufendorf's Moral and Political Philosophy," First published Fri Sep 3, 2010, substantive revision Tue Mar 19, 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/pufendorf-moral/ . *20. "On the Duty of Man and Citizen, According to Natural Law," by Samuel von Pufendorf, 1673, Book 1, Chapter 12. *21. "On the Duty of Man and Citizen, According to Natural Law," by Samuel von Pufendorf, 1673, Book 1, Chapter 8. *22. "Discourses Upon Trade: Principally Directed to the Cases of the Interest, Coynage, Clipping, Increase of Money," by Dudley North, 1691, Introduction by Jacob H. Hollander, Ph. D., published by the Library of Economics and Liberty, http://www.econlib.org/library/YPDBooks/North/nrthDT0.html . *23. "Discourses Upon Trade: Principally Directed to the Cases of the Interest, Coynage, Clipping, Increase of Money," by Dudley North, 1691, Section: "A Discourse of Coyned Money." *24. "Isaac Gervaise on the International Mechanism of Adjustment," by J.M. Letiche, University of California, Berkeley, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1826295?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents . *25. "The System or Theory of the Trade of the World," by Isaac Gervaise, 1720, Section: "Of the Ballance of Trade." *26. "The System or Theory of the Trade of the World," by Isaac Gervaise, 1720, Section: "Of Gold and Silver, or Real Denominator." *27. "The System or Theory of the Trade of the World," by Isaac Gervaise, 1720, Section: "Of Companies." *28. "The System or Theory of the Trade of the World," by Isaac Gervaise, 1720, Section: "Of the Ballance of Trade." *29. "The Economics of Control, Prefigured by Sir James Steuart," by Ronald L. Meek, Science & Society, Vol. 22, No. 4 (Fall, 1958), page 301. Original work: "The Economics of Sir James Steuart," Samar Ranjan Sen, 1957. *30. "An Inquiry into the Principles of Political Economy," by James Steuart, 1767, Chapter 7. *31. "An Inquiry into the Principles of Political Economy," by James Steuart, 1767, Chapter 20. *32. "An Inquiry into the Principles of Political Economy," by James Steuart, 1767, Chapter 3. *33. "An Inquiry into the Principles of Political Economy," by James Steuart, 1767, Chapter 14. *34. "An Inquiry into the Principles of Political Economy," by James Steuart, 1767, Chapter 18. *35. "An Inquiry into the Principles of Political Economy," by James Steuart, 1767, Chapter 11. *36. "The Wealth of Nations," by Adam Smith, 1776, Book 1, Chapter 5. *37. "Thomas Robert Malthus, (1766-1834)," from the Concise Encyclopedia of Economics, published by the Library of Economics and Liberty, http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/bios/Malthus.html . *38. "The Grounds of an Opinion on the Policy of Restricting the Importation of Foreign Corn," by Thomas Malthus, 1815. *39. "The Life and Economic Contributions of Simonde de Sismondi," by Margaret Gladys Sheldrick, Boston University, 1925. *40. "Political Economy," by Jean Charles Léonard Simonde de Sismondi, 1815, Chapter 2. *41. "Political Economy," by Jean Charles Léonard Simonde de Sismondi, 1815, Chapter 6. *42. "Political Economy," by Jean Charles Léonard Simonde de Sismondi, 1815, Chapter 2. *43. "Thomas Hodgskin," published by the Online Library of Liberty, http://oll.libertyfund.org/people/thomas-hodgskin . *44. "Labour Defended against the Claims of Capital," by Thomas Hodgskin, 1825. *45. "Nassau William Senior," published by the Online Library of Liberty, http://oll.libertyfund.org/people/nassau-william-senior . *46. "Three Lectures on the Rate of Wages," by Nassau Senior, 1830, Preface. *47. "The History of German Political Economy," by T.E. Cliffe Leslie, 1875. *48. "The Part Played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man," by Friedrich Engels, May-June 1876. *49. "Edward Carpenter: Red, Green and Gay," by Sheila Rowbotham, September, 2009, SocialismToday, Issue 131. *50. "The Value of Value Theory," by Edward Carpenter, 1889. *51. "Thorstein Veblen (1857-1929)," by the Concise Encyclopedia of Economics, published by the Library of Economics and Liberty, http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/bios/Veblen.html . *52. "The Instinct of Workmanship and the Irksomeness of Labor," by Thorsten Veblen, 1898-99, American Journal of Sociology, Volume 4. *53. "EJ Mishan obituary," published by the Guardian, Nov. 7, 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/nov/07/ej-mishan . *54. "The Costs of Economic Growth," by Ezra J. Mishan, 1967, Part 4, Chapter 13: Concluding Remarks, Page 172. . *55. "Obituary: Bert Hoselitz, Economics," published by the University of Chicago Chronicle, March 9, 1995, Volume 14, No 13, http://chronicle.uchicago.edu/950309/hoselitz.shtml . *56. "International Labor Movement in Transition," edited by Adolf Sturmthal and James G. Scoville, Chapter 2: The Development of a Labor Market in the Process of Economic Growth, by Bert F. Hoselitz, Page 34. *57. "Dietzgen, Joseph (1828-88)," from the Encyclopedia of Marxism at Marxist Internet Archive (MIA), https://www.marxists.org/glossary/people/d/i.htm#dietzgen-joseph . *58. "Scientific Socialism," by Joseph Dietzgen, 1873. *59. "Robert Dubin (1916 - 2014): Obituary," published by the Eugene Register-Guard, http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/registerguard/obituary.aspx?pid=172692935 . *60. "Industrial Conflict," edited by Arthur Kornhauser and Robert Dubin, 1954, Part 1: Basic Issues Concerning Industrial Conflict, Chapter 3: Constructive Aspects of Industrial Conflict, by Robert Dubin, Page 46. *61. "Explorations in Economic Sociology," edited by Richard Swedberg, page 425. *62. "The Sociology of Organizational Change," by E.A. Johns, page 1. *63. "Industrial Conflict," edited by Arthur Kornhauser and Robert Dubin, 1954, Part 3: Dealing with Industrial Conflict, Section B: Efforts to Remove Sources of Conflict, Chapter 24: Basic Employment Relations, by Charles A. Myers, Page 319. *64. "American Work Values: Their Origin and Development," by Paul Bernstein, 1997, SUNY Press, page 26. *65. "Man, Work, and Society," edited by Sigmund Nosow and William H. Form, Part 2: The Meanings of Work, Chapter 1: Work Through the Ages, by Adriano Tilgher, Page 16. *66. "In Memoriam: Ernest Greenwood," published by the University of California, http://senate.universityofcalifornia.edu/inmemoriam/ernestgreenwood.htm . *67. "Man, Work, and Society," edited by Sigmund Nosow and William H. Form, Part 7: Professions, Chapter 2: Attributes of a Profession, by Ernest Greenwood, Page 208. *68. "Howard Reiter," published by the Arena, http://www.politico.com/arena/bio/howard_reiter.html . *69. "Blue Collar Workers," edited by Sar A. Levitan, 1971, Section: "Blue-Collar Workers and the Future of American Politics," by Howard L. Reiter, Page 104. *70. "Rainwater Delivers His Final Lecture at Harvard: Professor of Sociology Retires after 23 Years; Best Known for Work on Plight of Urban Poor," by Bryand D. Garsten, December 15, 1992, http://www.thecrimson.com/article/1992/12/15/rainwater-delivers-his-final-lecture-at/ . *71. "Blue Collar Workers," edited by Sar A. Levitan, 1971, Section: "Making the Good Life: Working-Class Family and Life-Styles," by Lee Rainwater, Pages 210-211. *72. " S.M. Miller Award Statement," by the American Sociological Association (ASA), 2009, http://www.asanet.org/about/awards/careerpractice/Miller.cfm . *73. "Blue Collar Workers," edited by Sar A. Levitan, 1971, Section: "Can Workers Transform Society?", by S.M. Miller and Martha Bush, Page 243. *74. "Dissertations on First Principles of Government," by Thomas Paine, 1795. *75. "A New View of Society," by Robert Owen, 1816, Essay 4. *76. "Eight Hours Must Come," by Robert Green Ingersoll, 1877. *77. "Labor Movement and Socialism," by Anton Pannekoek, 1908. *78. "Workers Councils," by Anton Pannekoek, 1936, Part 2. *79. "John MacLean, 1879-1923," by the Marxists Internet Archive (MIA), https://www.marxists.org/archive/maclean/ . *80. "Capitalists Everywhere Accept Marxism," by John Maclean, 1919. *81. "Michael Burawoy," published by the University of California, Berkeley, http://burawoy.berkeley.edu/ . *82. "Manufacutring Consent," by Michael Burawoy, 1972, Chapter 2: Toward a Theory of the Capitalist Labor Process, Page 28. *83. "Half Lenin, Half Gandhi: A biography of Ho Chi Minh seeks to illuminate the leader who for all his prominence preferred to remain a cipher," by Frances Fitzgerald, October 15, 2000, published by the New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/books/00/10/15/reviews/001015.15fitzget.html . *84. "The Communist Road to Power in Vietnam," by William J. Duiker, 1981, Chapter 2: The Rise of the Revolutionary Movement (1900-1930), Page 25. *85. "The Landlord," by Henry David Thoreau, 1843. *86. "Paradise (to be) Regained," By Henry David Thoreau, 1843. *87. "The Ego and Its Own," by Max Stirner, 1845, Part 2, Chapter II, Section 2. *88. "The Ego and Its Own," by Max Stirner, 1845, Part 1, Chapter II, Section 3, Sub-Section 2. *89. "The Ego and Its Own," by Max Stirner, 1845, Part 1, Chapter II, Section 3, Sub-Section 3. *90. "The Capitalist System," by Mikhail Bakunin. *91. "Revolutionary Catechism," by Mikhail Bakunin. *92. "Voltairine de Cleyre," by Sharon Presley, The Storm! (Winter 1979), http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/Anarchist_Archives/bright/cleyre/presley.html . *93. "Direct Action," by Voltairine de Cleyre. *94 "Fellow Worker Eugene V Debs," published by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), http://www.iww.org/history/biography/EugeneDebs/1 . *95 "The Common Laborer," by Eugene V. Debs, 1890. *96 "Revolutionary Unionism," by Eugene V. Debs, 1905. *97. "Industrial Unionism," by Eugene V. Debs, 1905. *98. "The Conquest of Bread," by Peter Kropotkin, 1892, Chapter 3, Part I. *99. "The Conquest of Bread," by Peter Kropotkin, 1892, Chapter 3, Part I. *100. "The Conquest of Bread," by Peter Kropotkin, 1892, Chapter 6, Part I. *101. "Parsons, Lucy Gonzales," by William Loren Katz, published by the Zinn Education Project, https://zinnedproject.org/materials/lucy-gonzales-parsons/ . *102. "The Principles of Anarchism," by Lucy Parsons. *103. "Tolstoy the peculiar Christian anarchist," by Alexandre Christoyannopoulos, published by Anarchy Archives, http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/Anarchist_Archives/bright/tolstoy/chrisanar.htm . *104. "To the Tsar and his Assistants," by Leo Tolstoy, 1901. *105. "Freedom, a History of US: Joe Ettor," published by PBS, http://www.pbs.org/wnet/historyofus/web09/features/bio/B08.html . *106. "Industrial Unionism: The Road to Freedom," 1913, Section: Our Principles -- Our Aims. *107. "The Onward Sweep of the Machine Process," by Nils H. Hanson, 1913. *108. "The Onward Sweep of the Machine Process," by Nils H. Hanson, 1913. *109. "Industrial Socialism," by Frank Bohn and William D. Haywood, Part 1: Industrial Slavery. *110. "Industrial Socialism," by Frank Bohn and William D. Haywood, Part 2: Industrial Progress, the Growth of the Machine Process. *111. "When Should a Woman Avoid Having Children?," by Margaret Sanger, 1918. *112. "Notes on Address before the Woman Rebel Trial," by Margaret Sanger, 1914, Section: Woman and Morality. *113. "Errico Malatesta," by Ray Cunningham, published by Flag.Blackened.Net, from "Anarchism's greatest Hits No. 2," https://flag.blackened.net/revolt/ws/errico48.html . *114. "Anarchist Propaganda," by Errico Malatesta. *115. "Rudolf Rocker (1873 - 1958)," published by Flag.Blackened.Net, http://flag.blackened.net/rocker/ . *116. "Anarchism and Anarcho-Syndicalism," by Rudolph Rocker. *117. "The Reproduction of Daily Life," by Fredy Perlman, 1969.

|

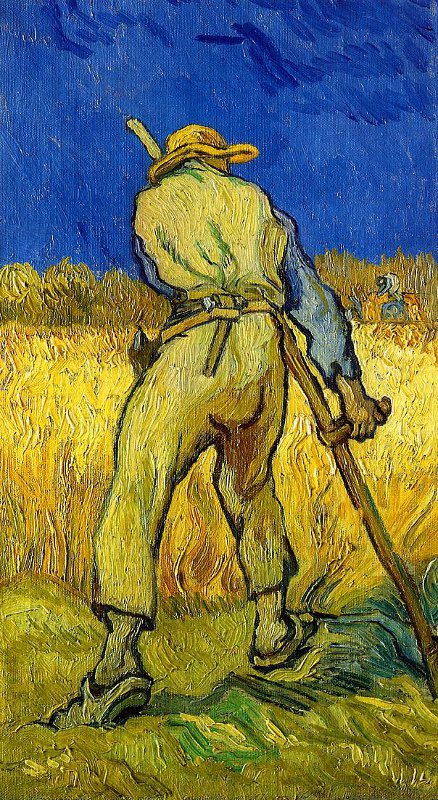

,_Vincent_van_Gogh_(1889).jpg)

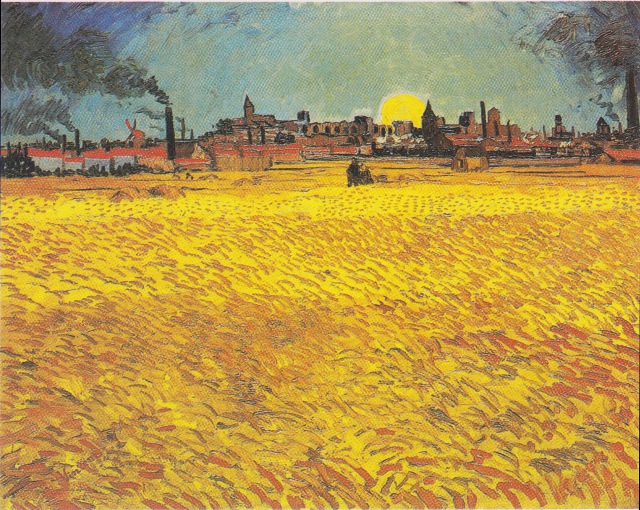

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

.jpg)